“Nappy Headed Hos”: Frenetic Inactivity and Displacement of Blame in the Don Imus Incident

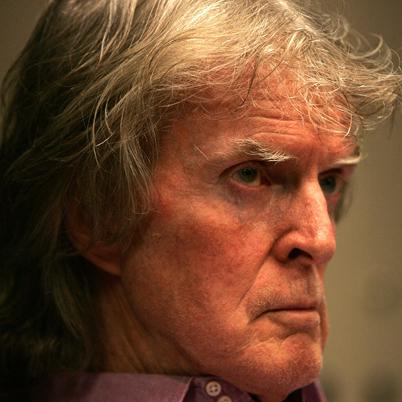

On April 4, 2007, shock jock Don Imus referred to the Rutgers women’s basketball team as "nappy headed ho's" following their Cinderella Story NCAA playoff run that left them the number 2 women’s team in the nation after losing to Tennessee in the finals the night before. It is hardly surprising that a shock jock generated interest and ratings with material that could be considered offensive by many. What was interesting in this case, however, was the ensuing furor that eventually cost Imus his position, as his comment became a “media event,” an iconic incident taking on importance in key symbolic public debates surrounding race and popular culture.

To investigate this media event, we examined all articles that mentioned the event in four of the five most widely read newspapers nationally, and a selection of nine regional papers from across the country during the week following the event. Although news is increasingly acquired from digital sources, research conducted in 2010 by the Pew Foundation demonstrates that mainstream print news media continues to serve as the primary source for the vast majority of media stories, including what is considered “alternative media.” In our analysis, we highlighted that this event actually received more media coverage than the entire NCAA women’s tournament. This is consistent with the dearth of serious media coverage of women’s sports in general, and illustrates how the scant coverage that women’s sports receives tends to be sensationalistic. For more detailed discussions of this problem, see the report on gender and sports media by two of the authors of this paper.

Several points of analysis struck us as pertinent to understanding the ways that media limits discussions on key issues. First, the story became one that centered on race and racism, despite the gendered, classed and heterosexist implications of the comment. The majority of the stories framed the story as being centrally about race (77.7%), while less than half highlighted the gendered implications, and none mentioned class or heterosexism. We argued that the Imus/ Rutgers University women’s basketball media event and the subsequent assignation of blame operated to make it appear as if race and racism are a problem of the past, with the exception of a few problematic individuals. Specifically, lambasting Imus makes it seem as if racism has been eradicated, while masking continued structural inequalities faced by non-white individuals, the continued prevalence of racism, and the general public’s complicity in this continuation. Given the regularity with which Imus’ show and other similar programs use racially charged language, the public shock and surprise over his comment might be more noteworthy than the comment itself. In this case, Don Imus’ framing contradicted the carefully constructed image of college sports as an accepted route to legitimation and accreditation for working class and low income non-white individuals. His comments reveal the subtle and not so subtle ways race continues to shape the opportunities of individuals, undermining cultural believes of a post-racial society.

Second, to re-establish this myth, the mass media took on the role of confessor and arbiter of justice, demanding the firing of Imus. However, once Imus was fired, his redemption began. Prior to his firing, only 10% of the articles gave him a positive frame, compared to 18% after. Moreover, following his apology, there was a subsequent displacement of blame for Imus’ comments onto popular culture, and more specifically onto subordinate or “othered” aspects, such as marginalized racial groups. Media reports displaced blame for the comments Imus made onto the culture of shock jock radio (25.5%), the audience (22.9%), and media profit (20.7%). In addition, hip-hop culture (17.6%), popular culture (10.1%), and black culture (5.9%) were framed as responsible for contributing to a cultural context that normalized such references.

It is important to note that, when taken together, the three dominant frames displaced blame onto a generalized, anonymous audience. The classic neoliberal conflation of free market and freedom emerged, as mainstream print news media criticized Imus’ statements, while simultaneously protected his right to broadcast. Undergirding this logic is a neoliberal valuation of profit that was conflated with democratic choice and freedom of speech. In other words, because controversial and titillating comments are presumed to generate larger audience shares and therefore more profit, understanding such comments as simply freedom of expression misses a large part of the picture. Media tends to defend all media content as essential to the maintenance of a free press, especially ideologies that support ratings and profits. This defense is presented as free market democratic choice, while little attention is given to the economic inequality that fundamentally undercuts democracy by limiting access to speech to a select few. Racism and the furor surrounding it in this instance became just another profit generating spectacle.

Third, the role of the media in defining the debate is crucial because this then sets the context in which public life is understood. More importantly it plays a role in defining the parameters for public involvement. At the same time, public debate in media forums provides an outlet for sentiment that may undermine impetus for change. Here, we coined the term “frenetic inaction” to refer to the tremendous amount of media coverage which occurred in a short time frame that ultimately did little to address the problems of racism, classism, sexism, and heterosexism in wider society. In the mainstream news media coverage of the controversy, racism was debated, discussed, defined, and identified all at the individual level, or it was displaced onto popular or Black culture. At the same time, the media frames left unchallenged the structurally embedded forms of inequality in dominant culture.

We argue this “frenetic inactivity” is an essential part of media events, one that operates to undermine meaningful social action by channeling energy and focus into specific understandings that often are limited to micro-level debates. Indeed, Imus returned to radio on December 7 of the same year, albeit in a much smaller market. In following the story, debating the points, and participating in the various media framings, the media created a specific set of frames for audiences to experience the event, one that generated a sense of civic engagement in the absence of meaningful social change.