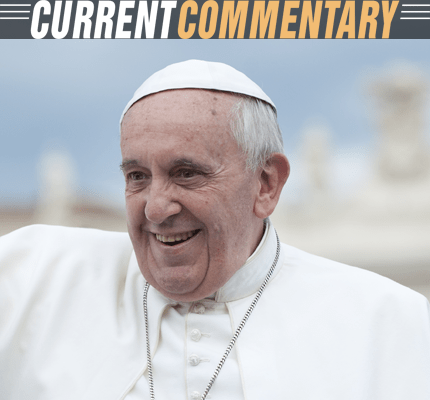

Fake News, Real Solutions: Journalism History and Pope Francis’ Message for World Communications Day 2018

Between Time magazine issuing a correction regarding its cover image of a crying toddler and President Trump making a false claim about the number of U.S. citizens who have been killed by undocumented immigrants, partisans on all sides have had ample opportunity to cry “fake news!” in recent days. And, as new research from the Pew center shows, Americans are woefully bad at distinguishing between facts and opinions in news articles. The problem of “fake news” clearly is not going away. However, many audiences have overlooked one important response to the issue: Pope Francis’ message for World Communications Day this May.

Ever since Pius XI launched Vatican Radio in 1931 with a blessing for the entire world, Popes have been active mass media leaders on an international scale. Paul VI reinforced this tradition in 1967 by inaugurating World Communications Day (WCD), an annual occasion for the Pope to recognize and reflect on the global impact of communication technologies. Since Pius XI and Paul VI, our media sphere has changed tremendously. Mainstream journalists now operate within the multilateral free-for-all of social media, and humanity is racing toward a time when everyone can communicate instantaneously with everyone else. In this vast, diverse, and dynamic setting, it comes as no surprise that many people are not aware that WCD exists, let alone that Pope Francis’ 2018 WCD message directly addressed fake news.

Fake news is disinformation that seeks advantage via manipulative and deceptive rhetoric. Online, it reverberates within homogenous communities until it is greatly amplified and widely distributed, often by unwitting dupes. This phenomenon is so widespread that many scholars claim we have entered a mediated “post-truth” era, and this view presents a formidable challenge to our understanding of communication and journalism’s role in fostering public goods. World Communications Day was celebrated on May 13, 2018, and studying Francis’ message, “‘The truth will set you free:’ Fake News and Journalism for Peace,” provides an opportunity to learn how lessons from both the Christian and journalistic traditions can inform ethical communicators.

At base, fake news rests on an ethical problem with which Religion and Communication scholars have grappled since antiquity. When visiting Sophists taught Athenians relativism and speech that pursued personal power over the common good, Plato and Isocrates were quick to counter with a philosophy of communication growing from interpersonal love, collaboratively reaching for divine truth, and valorizing public discourse as a patriotic call to community. On the other side of the Mediterranean, the Jewish tradition had been working with God’s prohibitions against falsehoods for centuries when Jesus fulfilled all Mosaic Law, divinizing truth within Himself. These two traditions, Judeo-Christian and Greek, were expanded and united by early Church fathers such as Origen and Augustine to inspire a firm value for truth that characterized Western culture through the Middle Ages and well into the Renaissance. To be sure, some of what Western culture accepted as true turned out to be rooted in ignorance or prejudice, but faith in truth itself was a defining feature of Christianized Europe.

The Enlightenment period saw enormous advances in human understanding of nature and society, but as knowledge became more diffuse, “truth” became more contested. In place of identifying as dependent and familial “children of God,” educated Westerners moved toward a feeling of self-sufficient power that left God behind; as DesCartes declared, “I think, therefore I am.” The modern stress on individual over relational being tends to view rhetoric Sophistically as a tactical instrument, rather than socially as an interpersonal bond. Each new communication technology provided increasingly powerful ways to promote falsehoods and self-serving agendas. The news pamphlets of early modern Europe mixed reports of war and politics with tales of monsters and the supernatural. Many of the newspapers that helped fuel the American Revolution and French Revolution did so with fabricated stories. Even after the birth of a mass-circulation press in the 1830s, rumors and hoaxes still occasionally appeared alongside legitimate news.

Beginning in the mid-20th century, however, especially in the United States, information no longer flowed so freely to the masses. Powerful publishers and broadcasters controlled the distribution channels: newspapers, magazines, radio stations, and television networks. According to the gatekeeper theory developed by David Manning White and other scholars in the 1950s and ‘60s, journalists and media executives filter information before it reaches the public, by applying certain standards of “newsworthiness.” One such standard is accuracy—in order to maintain their credibility with a mass audience, publishers and broadcasters had a strong incentive to allow only factual information through the gates and to present it without bias.

Today, traditional media outlets have lost much of their influence to social media platforms. As Pope Francis suggested, and as many journalists have noted, when it comes to combatting fake news, it may be better to stop solely relying on institutional gatekeepers and affirm that people are “the best antidotes to falsehoods.” In an era when every individual with a social media account has become a gatekeeper, responsibility for truth falls on everyone. With this view, the long-term human development solution is education, or in Catholic terms “formation.” Simply put, people deserve a real education, because anyone who has been manipulated and duped by mass mediated lies is far from free.

Post-modern liberty requires media literacy and production training—the ability to both recognize and produce honest, ethical, and effective content. Grounding these arts within humanities disciplines such as religion, philosophy, rhetoric, and ethics instills a clear sense that, while a diverse media polyphony is a vibrant expression of humanity, truth transcends all partisan perspectives. Final judgments may be impossible for a diverse and liberal society, but knowing that some argumentation patterns are inherently valid and others patently specious helps us learn that truth is real. Understanding that some relational patterns are inherently oppressive while others are genuinely compassionate helps us appreciate the human in one another. Fake news transforms our two ontological horizons, the Real and the Other, into social fault lines; an ethical, critical, and discerning public is the best protection against further social upheaval.

The alternative to developing people who are sensitive to truth is an accelerating media spin cycle that allows division and hatred to flourish. To conclude his 2018 WCD message, Francis explained that communication is fundamentally relational and constitutive -- “Informing others means forming others . . . ensuring the accuracy of sources and protecting communication are real means of promoting goodness, generating trust, and opening the way to communion and peace.” Within this view, truth is inter-subjective and communal, touching everyone, and it is precisely this shared quality that ties truth to freedom and peace. We all live in the same shared world; it grows and changes, but it is always our world that we build up and tear down together.

Back in 1931, Pius XI’s first radio address drew a global and record-setting audience, and today Pope Francis is but one voice within a crowded media sphere. Communication history demonstrates that Francis’ lesson is worth heeding: to marginalize fake news and build a healthier media environment, we need people who champion critical inquiry, truth, and one another to develop a post-modern “journalism for peace.”

References

- Francis. 2018. “’The truth will set you free’: Fake news and journalism for peace.”

- Pressman, Matthew. 2018. On Press: The Liberal Values that Shaped the News. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Shoemaker, Pamela J., and Vos, Tim P. 2009. Gatekeeping Theory. New York: Routledge.

- Stephens, Mitchell. 1988. A History of News: from the Drum to the Satellite. New York: Penguin.

- White, David Manning. 1950. “The ‘Gate Keeper’: A Case Study in the Selection of News.” Journalism Quarterly 27: 383–390.

- White, David Manning. 1964. “Introduction to the Gatekeeper.” In People, Society, and Mass Communication, edited by Lewis Anthony Dexter and David Manning White, 160–161. New York: Macmillan.

Further Reading

- Bro, Peter, and Walberg, Filip. “Gatekeeping in a Digital Era,” Journalism Practice 9, No. 1 (2015), 92-105.

- Herbst, Jeffrey. “How to Beat the Scourge of Fake News,” Wall Street Journal, December 11, 2016.

- Jacobson, Linda. "The Smell Test." School Library Journal 63, No. 1, (Jan. 2017), 24-28.

- Maksl, Adam; Craft, Stephanie; Ashley, Seth; and Miller, Dean (2017). The Usefulness of a News Media Literacy Measure in Evaluating a News Literacy Curriculum. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator 72, No. 2, 228-241

- Rosenwald, Michael (2017). “Making Media Literacy Great Again.” Columbia Journalism Review 56, Issue 2 (Fall 2017), 94-99.

- Rose-Wiles, Lisa. “Reflections on Fake News, Librarians, and Undergraduate Research.” Reference and User Services Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2018), 200-204.

- Schneider, Howard (2018). "Reading between the Lines: News Literacy Is an Essential Part of Education for 21st-Century Students." Quill 106, no. 1, (2018), 8-15.

- Strauss, Valerie. “The News Literacy Project takes on ‘fake’ news — and business is better than ever.” WashingtonPost.com, March 27, 2018.

Media Experts

- Msgr. Dennis Mahon, Seton Hall University

- Matthew Pressman, Seton Hall University

- Jon Radwan, Seton Hall University