Inflammatory Rhetoric of Othering in Times of Humanitarian Crises

By Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager, Ph.D.

Jean-Paul Sartre once famously stated: “l’enfer c’est les autres” (Hell: it’s the Others). More than half a century later, the most powerful political leaders have adopted and normalized the dangerous approach of demonizing the Other in their anti-immigrant and anti-refugee politics and rhetoric, which are currently redefining identity politics and reshaping borders around the globe.

When Donald Trump became U.S. President, his “America first” slogan quickly turned into a practice of white, misogynist, capitalist patriarchy, with strong xenophobic tendencies. Having normalized the term “Islamic terrorism,” introduced the controversial Muslim travel ban, and requested surveillance of certain mosques, the Grabber-in-Chief decided to build a wall to separate the United from Mexico – whose bad hombres were rapists, bringing drugs and crime to the country. Alarmingly, this presidential rhetoric both ignited hatred of the Other and spread like fire. Now, the echo of “Trumpian” rhetoric can be heard in multiple corners of the world, including Europe, whose anti-immigrant rhetoric exemplifies the Eurocentric West-and-the-Rest approach.

Italian interior minister Matteo Salvini acts like Trump’s Doppelgänger, having adopted “Italians first” as his leading ideology. In addition to promises of an economic reboot (Italy-first), Salvini’s slogans “gli italiani prima di tutto!” (the Italians first and foremost!) and “al centro – gli italiani!” (the Italians to the center!) contain promises of restoring national pride, promises that are tempting for the Italians in these turbulent times. In 2015, Salvini organized rallies with the slogan “Stop the Invasion!” Capitalizing on the refugee crisis, Salvini harshened the anti-immigrant rhetoric and accused thousands of illegal immigrants of stealing, raping innocent Italians, and drug-dealing.

Salvini had already turned away a boatload of more than 600 African refugees on a ship named Aquarius. Similarly, on the night of July 30, 2018, nearly 350 people were taken back to Libya – not an EU-approved “safe landing” point. Salvini responded with “La pacchia è finita!” (“The party is over”) and Mussolini’s famous “Tanti nemici, tanto onore!” (“Many enemies, much honor!”)

Speaking of Mussolini, Pierre Moscovici, the EU’s economics affairs commissioner, has said that the current political situation in Europe resembles the 1930s, when Germany’s Hitler and Italy’s Mussolini were in power. Moscovici has voiced fears that “little Mussolinis” are on the rise in Europe. Nonetheless, Salvini continued with anti-immigration rhetoric during the recent European conference on security and immigration. In response to Luxembourg’s foreign minister Jean Asselborn’s concern about Europe’s ageing populations, Salvini conceptualized migrants as undesired slaves: “Maybe in Luxembourg there’s this need for migrants, in Italy here’s the need to help our kids have kids, not to have new slaves to replace the children we’re not having.”

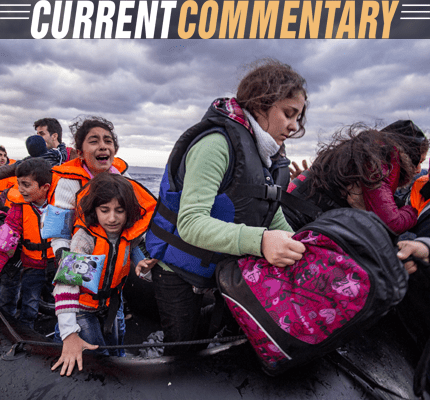

Salvini is supported by other EU ultra-nationalist leaders from Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, and Hungary. Salvini emphasized that Italy will “no longer be Europe’s refugee camp,” and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán added: “Hungary has shown that we can stop migrants on land. Salvini has shown migrants can be stopped at sea.” Gradually, rhetorical framing of the Other as a dangerous invader, and references to fascism have become the new communicative norms not only in Central and Eastern Europe and Italy, but also in Greece – another migrants’ first point of entry. The mayor of Lesbos, Spyros Galinos, warned that immigrant detention centers had started to resemble “concentration camps.” Nonetheless, Greece recently imprisoned Sara Mardini, a Syrian refugee and an Olympian swimmer, who saved 18 refugees in 2015 by swimming their waterlogged dinghy to the shores of Lesbos. Mardini is accused of people smuggling, espionage, and membership in a criminal organization. Apparently, when the fear of the Other dominates the national sentiment, rhetorical criminalization of humanitarian actions is another natural outcome.

Xenophobia is also growing in Sweden and Denmark. Today’s Danish national rhetoric equates refugees with the social underworld and frames them as “ghetto.” According to this rhetoric, new Danish law should separate “ghetto parents” from “ghetto children,” to teach the latter proper Danish values (e.g., Christmas, Easter, and Danish language), with noncompliance resulting in a stoppage of welfare payments. Politicians’ description of the ghettos has become increasingly sinister, substituting “integration” with “assimilation.” Danish Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen warned that ghettos could “reach out their tentacles onto the streets by spreading violence.” Historically, criminal organizations, including the Italian mafia, were framed as La Piovra (the octopus), so the correlation with brutal crimes is inevitable. Similarly, Sweden – a country that once prided itself on being the humanitarian superpower – is now strongly divided by migration. The humanitarian crisis there has overwhelmed social services and caused such fury that some refugee accommodation centers have been set on fire. Now, migration informs Swedish views on everything, and is rhetorically inseparable from crime, hospital waiting times, schools, and pensions.

Xenophobia and Islamophobia are also causing political crises in Germany (once the most pro-refugee country) and France (whose president is still the most pro-European leader). German national rhetoric has changed from encouraging the Willkommenskultur (the culture of open welcome) to warning against Messermigration (“knife migration,” which associates migrants with violence with an Islamic twist). After his 2010 national bestseller, Deutschland schafft sich ab (Germany Abolishes Itself), which demonized Arabs and Turks, former Berlin senator of finance Thilo Sarrazin published another Islamophobic book, Feindliche Übernahmen (Hostile Takeovers). Far-right street violence has increased in response to an alleged assassination of a German by a Syrian and an Iraqi refugee. Numerous protesters took to the streets, waving German national flags and chanting Nazi-era slogans. The demonstrators displayed placards that read “stop the refugee flood” and “defend Europe,” the latter adorned with an image of an automatic rifle. Even France, whose President Macron once openly praised German Chancellor Merkel for opening borders and saving Europe’s “public dignity,” has introduced a new bill that would criminalize illegal border crossings. Macron’s skilled rhetoric has shifted toward “humane and firm”: firm standing on firm borders, protecting Europe from the undesired, inassimilable, and threatening Others.

In her book, No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need, Naomi Klein writes, “If there is a single, overarching lesson to be drawn from the foul mood rising around the world, it may be this: we should never, ever underestimate the power of hate. Never underestimate the appeal of wielding power over “the Other,” be they migrants, Muslims, Blacks, Mexicans, women, the other in any form. Especially during times of economic hardship, when a great many people have good reason to fear that the jobs that can support a decent life are disappearing for good.” Sadly, we seem to live, to communicate, and to Other “by the book” – specifically, by Klein’s book. America and Europe are on the edge of rethinking and re-shifting their borders – geographical, political, and humanitarian. Speaking to the economic panic, and to the resentment felt by large segments of America and Europe about the changing faces of their countries, nationalist leaders create the feeling of dangerous nostalgia for the lost, mono-cultural worlds of a past that no longer exists, and that cannot exist in the future. It is time to embrace the globalizing realities, and to start thinking – and communicating – OtherWise.