Reflections on the 100th Anniversary of the 19th Amendment in NCA’s Quarterly Journal of Speech

Today is the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted white women the right to vote. In a special issue of NCA’s Quarterly Journal of Speech, the authors explore what this Amendment has meant, and its ramifications for today’s women’s rights efforts. In the introduction, Karrin Vasby Anderson, Professor of Communication Studies at Colorado State University, summarizes the issue’s articles, which examine how the stories we tell about the 19th Amendment hide the contributions of women of color to the expansion of voting rights in the United States. The stories we tell about the 19th Amendment also obscure the fact that marginalized groups have been denied voting rights and access to full citizenship throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Despite the passage of the 19th Amendment, non-white women were excluded from voting in the 20th century through a variety of means, including laws that prohibited Indigenous people from voting, laws that excluded people of Japanese and Chinese ancestry from citizenship, a scarcity of polling places for Latinx citizens, and Jim Crow laws that kept Black Americans from voting. The essays in this special issue challenge the traditional narrative of the women’s movement on three fronts: time or chronology, protagonists, and the nature of citizenship.

Time

Anderson notes that the issue disrupts the conventional narratives around the women’s rights movement. In particular, Catherine Helen Palczewski’s essay in the issue addresses the chronology of the U.S. women’s rights movement. The movement is often said to have begun in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Convention and to have ended with the ratification of the 19th Amendment. However, according to Palczewski, this history is the result of “careful memory work” by History of Woman Suffrage co-authors Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who centered themselves as the leaders of the movement and Seneca Falls as its birthplace.

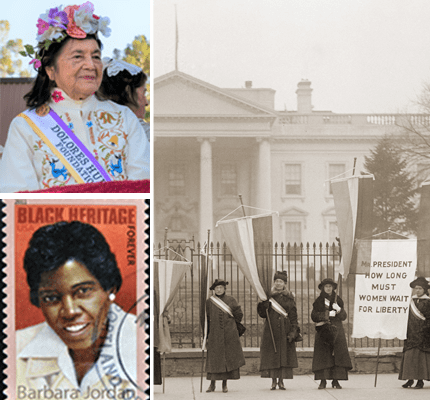

Belinda A. Stillion Southard’s essay addresses the relevance of the National Women’s Party (NWP) to today’s Black Lives Matter protests. The essay examines how NWP members prepared themselves to experience state-sanctioned violence. When members protested between 1917 and 1919 in front of the White House, they were often arrested; nevertheless, they later returned to the picket line. Today, police sometimes use tear gas, rubber bullets, and other violent tactics against peaceful Black Lives Matter protestors, demonstrating the continued relevance of the NWP and its tactics.

Two other essays in the issue also address how we remember the women’s rights movement. Jessica Enoch analyzes 19: The Musical, a musical about suffragists in honor of the centennial of the 19th Amendment. Enoch considers how the musical attempts to broaden the typical narrative of the women’s suffrage movement to one that is more inclusive. Yet, according to Enoch, the musical falls short in critiquing the racist positions held by suffragists. Alyssa A. Samek addresses the ways in which the 1977 International Women’s Year Conference in Houston, Texas, engaged with the history of women’s suffrage in the United States.

Protagonists

In addition to unsettling the familiar chronology of the women’s rights movement, the special issue’s essays also challenge the typical roster of protagonists and antagonists by offering narratives about intersectional experiences in the women’s movement. Stacey K. Sowards’ essay explores the impact of Dolores Huerta. Huerta, a co-founder of the United Farm Workers Movement, is best known as a labor activist, but also advocated for voter registration and other rights. Likewise, Carly S. Woods’ essay examines Barbara Jordan, a congressional representative from Texas who also advocated for voting rights. Jordan’s work highlights the importance of intersectionality within the women’s movement.

Two essays address women’s suffrage in the 19th and 20th centuries. Leslie J. Harris analyzes how anti-suffrage arguments in the 19th and early 20th century used white supremacist tropes that depicted Black women as hypersexual and, therefore, unfit citizens. These anti-suffragists also asserted that white women would become degraded by leaving the home and, therefore, that voting represented a threat to white civilization. Zornitsa D. Keremidchieva looks beyond our borders, examining the Third Communist International (Third Comintern), which was founded in 1919. Keremidchieva explores the intersection of women’s rights and anti-colonialist and anti-capitalist work.

Although the 19th Amendment was ratified 100 years ago, the struggle for voting rights continues. For example, in many states, people with felony convictions cannot legally vote, even after they have served their sentence. Lisa A. Flores and Mary Ann Villarreal address the ways in which narratives of “ignorance” related to voting are racialized. In recent years, voters of color have been convicted for voting when they were not legally able to, despite not knowing that they could not vote because of their residency status or past felonies. These “ignorant” voters of color are cast as a threat to the nation in media coverage. In contrast, “ignorant” white poll workers who cause delays or prevent people from voting are described as making “honest mistake[s].” Thus, the poll workers’ “ignorance” casts them as innocent, rather than a threat.

Stephanie A. Martin and Isra Ali also address contemporary issues. Martin considers why some Evangelical women shifted away from their support for Donald Trump after the 2016 election and how their political engagement is changing. Ali analyzes how young Muslims, particularly women, engage in meme culture online. According to Ali, by sharing and engaging with memes about the experiences of young Muslims, these young women articulate their identities as both Muslims and young American citizens.

Citizenship

Finally, some essays in the issue address the nature of citizenship beyond voting rights. Inbal Leibovits’ essay examines how homeless women exist on the margins of citizenship. They may be legal citizens, but they do not fit within the norms of “good citizens” and thus lack political power. The essay explores how homeless women can advocate for themselves and how public discourse can better include and recognize marginalized perspectives. Ashley R. Hall introduces an Afrafuturist Feminist (AFF) rhetorical approach, which focuses on how Black women across time (past and present) threaten white supremacy through truthtelling. Using AFF, Hall considers how Assata Shakur and Cardi B affirm their agency and tell their stories as Black women.

V. Jo Hsu’s essay challenges the way in which voting is framed as the primary method of citizen engagement in democracy. United States citizens are often told that voting is the most important thing that they can do. Yet, historically, organizing around voting, including women’s rights, often reinforced the white, cisgender, heterosexual citizen as the norm. Full citizenship was withheld from those who did not meet these conditions; for example, in the 20th century, Black Americans were often prevented from voting if they did not meet certain economic or educational requirements. Today, voters in U.S. territories have no vote in U.S. presidential elections. The essay challenges the ways in which the women’s rights movement has placed faith in the vote as a key means of democratic change.

Conclusion

This essay has offered a brief introduction to the articles in the new issue of NCA’s Quarterly Journal of Speech. The articles offer varied perspectives on the women’s movement and show how much more can be done in studying and promoting broad democratic engagement. As Anderson writes, “This special issue is, then, a set of opening remarks, a speculative preface, and an invitation to join the conversation about the next hundred years of gender and democratic engagement at the intersections.”

The free-to-access issue is publicly available on NCA’s website.