Voices of Dissent Are Shaping the Public Agenda

Important messages we hear and see in the media are prompted by strong voices of dissent. They have dared to make public what those in power have kept secret and do not want public. We live in a time when the confluence of strong voices of dissent confronting power are shaping our public agenda—voices of whistleblowers, #MeToo, and media journalists.

We live in a time when the confluence of strong voices of dissent confronting power are shaping our public agenda—voices of whistleblowers, #MeToo, and media journalists.

Whistleblowers

Whistleblowers have prompted us to debate what should be made public vs. what should be kept secret. At a time when trillions of new pages of text were being classified each year and more than 4.8 million people had security clearance, Edward Snowden was charged with disclosing “unauthorized national defense information.” Ironically, since then Snowden has been entrapped in asylum in Russia, a country that is intolerant of freedom of information. His leak of surveillance data occurred more than seven years ago, so of late he has received little media attention.

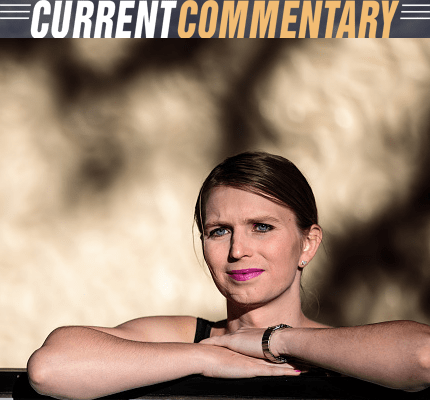

However, Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange, whose leaks were also at the time of Snowden’s, are again in the news. After serving seven years of a 35-year sentence, on March 8 this year, Manning was put back in solitary confinement for 62 days because she would not respond to Grand Jury questions about Assange and WikiLeaks. While Manning was in prison, London police arrested Assange, removing him from seven years of asylum in its Ecuadorian Embassy. He awaits an extradition hearing in February next year and faces an 18-count indictment by the United States. If Assange is extradited, Manning has vowed she will not testify against him, even if granted immunity. She probably will face new charges.

We may again hear Manning’s gritty story of sending 700,000+ sensitive documents to Assange at WikiLeaks, of not just seeing statistics and information, but also seeing people. For journalist Christopher Hedges, Assange’s indictment is troubling. He sees Assange as a fellow journalist and asserts that it is “the role of journalists to give a voice to those who without us would have no voice, to hold the powerful to account, to give the forgotten and the demonized justice, to speak the truth.”

The most famous whistleblower-survivor may be former Rand Corp analyst Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times. Ellsberg laments that charging Assange with espionage constitutes “a direct attack on the First Amendment, an unprecedented one.” We have reached a point of debating whether those who “reveal classified secrets that endanger other people’s lives” are good guys, according to Jim Geraghty in the National Review.

The #MeToo Movement

#MeToo voices of dissent have put sexual dignity vs. power on the public agenda. Dozens and dozens of sexual assaults by the powerful have been exposed by #MeToo activists. Since April 2017, more than 265 celebrities, politicians, CEOs, and others have resigned or were fired. Righting the wrongs of sexual imposition is a continuing matter on our public agenda. Television personality Diana Falzone, reflecting on her interviews with women in the media who have spoken out, argues: “The very same people who publicly applaud you for speaking up about bad behavior will never hire you into their own organizations because you are forever pegged as a whistleblower and a troublemaker.”

In an interview with Brian Stelter on CNN’s Reliable Sources, former CBS correspondent Scott Pelley said, “I lost my job at the evening news because I wouldn’t stop complaining to management about the hostile work environment.” With the exit of those at the top of the network, including CEO Les Moonves, who resigned because of sexual accusations, CBS made major changes in personnel. Pelley now predicts good times ahead.

Journalists’ Voices

Journalists are expected to be objective, but because President Trump has generated provocative questions and counts of “Pinocchios,” their voices have shaped our current public agenda of truth vs. falsity. The Washington Post tallied 10,111 false and misleading statements made by Trump in 828 days. When CNN’s Jim Acosta raised questions about wrongdoing, the President singled him out in one of his many cries of “fake news” and “enemies of the people.” Such rhetoric endangers both journalists and learning what is true and false. Acosta says he has received more death threats than he can count.

In autocratic countries, reporters are attacked. Sixty-five journalists and media workers were killed worldwide in 2017, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF). Thanks to Peter Finn and Sari Horwitz, we learned of “audio and video recordings indicating the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi was killed during his visit to the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul.”

Journalists are doing what they should do when they ask for and then report the facts. They expect us to carefully weigh what they say. It’s up to those of us who research, teach, and practice communication to denounce branding journalists as enemies of the people. It’s our responsibility to honor dissenting voices.

References

Gorden, W. I., Infante, D. A., & Graham, E. E. (1988). Corporate conditions conducive to employee voice: A subordinate perspective. Employee Responsibilities and Rights, 1(2), 101-111.

Gorden, W. I. (1988). Range of employee voice. Employee Responsibilities Rights Journal, 1, 283-299.

Kassing, J. (2011). Dissent in Organizations. New York: Wiley.

“Wikileaks source jailed for contempt is freed” Chelsea Manning. (2019, May 10). BBC News 10 May 2019. Retrieved from www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-48223178.

Photo credit: Jack Taylor/Getty Images