WeToo and Breaking the Silence with #MeToo

By William I. Gorden, Ph.D.

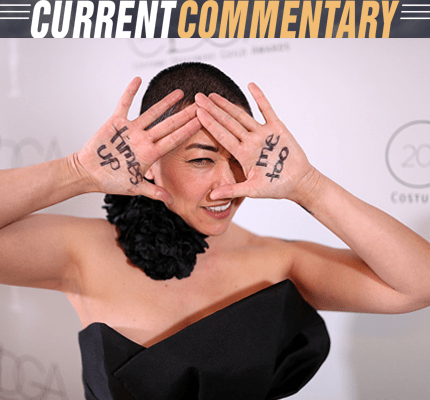

This photo of costume designer Ane Crabtree at the Designers Guild Awards on February 20, 2018 and the broad media coverage that followed illustrate how a movement against sexual violence and inequality in the workplace gained national and then worldwide attention.

#MeToo and Time’s Up awakened women to break their silence. The #MeToo movement won followers when its person-centered hashtag splashed across social media. Time’s Up won support because of its fundraising tweets. President Trump unintentionally blessed the movement in his defense of nominee for Justice of the Supreme Court Brett Kavanaugh, by lamenting that #MeToo is “very dangerous” for powerful men.

...the #MeToo movement “is a discourse alive with meaning and materiality.” I understand it as an expression where organizational, interpersonal, rhetorical, mass communication occur and more.

TIME magazine elevated the movement by naming as its 2017 Person of the Year “The Silence Breakers,” honoring not one individual, but all of the women involved in catapulting the #MeToo movement into the national narrative, as well as the cause as a whole.

In a forum organized by Robin Clair and published in the February 2019 issue of the Journal of Applied Communication Research (JACR), the case was made that the #MeToo movement “is a discourse alive with meaning and materiality.” I understand it as an expression where organizational, interpersonal, rhetorical, mass communication occur and more.

#MeToo grew out of the work environment. Civil rights activist Tarana Burke, an African-American, professional working woman, is credited as its founder. In the JACR forum, Clair, in reference to Burke’s knowledge of sexual harassment and racial oppression of women, asserts that “#MeToo came out of a nightmare, not just Tarana Burke’s nightmare, but the nightmares of far too many people.” The forum explicates how Communication scholars who study rhetorical influence in the work and political milieu cannot help but be part of the current fight for gender equity and an end to sexual assault.

WeToo lift our voices that tell herstory. Years ago, in a Speech in a Free Society course, I assigned a paper on foot binding, to tell how women were kept subordinate for ten centuries. In our country, herstory was a long battle by women to gain voting rights—rights that were opposed even by members of the clergy. In my small contribution to the JACR forum, I relate how traditional Jewish/Christian scripture silenced women yesterday and today; it parallels other religious scriptures, such as the Koran. Genesis 2:16-17 profiles Eve as God’s afterthought and responsible for the first couple being cast out of Eden. According to the Bible, her additional punishment was the pain of childbearing.

In the JACR forum, Hannah Delemeester asserts that “#MeToo breaks the silence by opening spaces for voices to speak.” Tyler Sorg explains, “Though unwanted within organizational culture, sexual harassment finds its way into an organization, sustains and prospers, and seldom leaves”—thus making silence normal. Male sexual imposition occurs in many forms of power over one with less: Clergy abuse of thousands of children, a boss’s quid pro quo of sex for a promotion or to prevent a firing, adult abuse of a babysitter, date rape, and beating a wife. In this country, approximately 1,500 women are killed each year by husbands or boyfriends, and about 2 million men per year beat their partners, according to the F.B.I.

In the forum, Debbie Dougherty writes, “I discovered that there is no such thing as an innocent bystander.” That is to say, those of us who learn of sexual assault are guilty if we frame it as “boys will be boys” or “girls cause it by the way they dress.” And, Paaige K. Turner reasons that “the personal is political”—that addressing sexual assault should be a matter of public policy.

#MeToo has upset the powerful. The New York Times (among other news outlets) has even named them. Since April 2017, more than 250 powerful people—celebrities, politicians, CEOs, and others—have been reported for sexual harassment, assault, or other sexual allegations. Many have resigned; others have been forced out, fired, prosecuted, and/or sued.

Some well-known victims have suffered from and responded to public humiliation, including Anita Hill, those drug-raped by Bill Cosby, intern Monica Lewinsky, and Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. These women are being heard. But Amanda Taub, in the February 11, 2019, New York Times, argued that the #MeToo “movement has had little effect on the broader problem of sexual abuse, harassment and violence by men who are neither famous nor particularly powerful.” And, questions submitted to Ask the Workplace describe the frustration and hurt felt by many sexually harassed/assaulted working women who are far from the public spotlight.

Posts to my website, Ask the Workplace Doctors, frequently are pleas from lower-level employees for advice, such as “About two weeks ago, this male coworker started touching, poking, and pretending to punch me in the jaw. He actually asked me to talk dirty to him about a week ago. In anger, I told some co-workers about my experience. They completely supported me but explained that I should have told him on the spot to stop. I don’t disagree but was in shock by his behavior, so I didn’t react the way I should have!” I introduce my students to dozens of such descriptions submitted to the site and to the advice we provide on how to cope with and deter such conduct.

In the JACR forum, Robin Clair described the sexual assault she had experienced by a male parent when she was babysitting. She sequestered it for years, as have others, until she shared it last year in a “Take Back the Night” march at Purdue University: “I will say that my spirit left my body and I heard myself screaming from where my mind stood, away from my body that was being assaulted.”

#MeToo and Time’s Up break years of silence and inequality. Silence today should be as much a part of the past as foot binding and suffragettes. Religious stories that depict women as an afterthought of Adam's rib should also be part of the past, as is serving coffee for the boss.

#MeToo and Time’s Up fight for dignity and respect. WeToo should help break the silence.

References

Ask the Workplace Doctors http://workplacedr.comm.kent.edu/ Series of Q&As in the category of Dating Coworkers

Alix Langone #MeToo and Time's Up Founders Explain the Difference Between the 2 Movements — And How They're Alike Time Updated: March 22, 2018

Robin Patric Clair, Nadia E. Brown, Debbie S. Dougherty, Hannah K. Delemeester, Patricia Geist-Martin, William I. Gorden, Tyler Sorg & Paaige K. Turner. #MeToo, sexual harassment: an article, a forum, and a dream for the future. Journal of Applied Communication Research, Volume 47, 2019 - Issue 2. Published online: February 11, 2019 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00909882.2019.1567142

Clair, R.P. (1993) The use of framing devices to sequester organizational narratives: Hegemony and harassment. Communication Monographs, 60, 113-135.

Gorden, W.I. Women Are Breaking the Silence: Time’s Up and #Me Too Published on LinkedIn October 1, 2018

GotQuestions.org “Question: Why did God put the tree of knowledge of good and evil in the Garden of Eden?

Rucker, P., Costa, R., Dawsey, J. and Parker, A. Defending Kavanaugh, Trump laments #MeToo as “very dangerous” for powerful men. Washington Post, September 26, 2018

Amanda Taub. #MeToo Paradox: Movement Topples the Powerful, Not the Ordinary. The New York Times, February 11, 2019

Zareian, Omid. Women as Seen in Islam. www dot famafrique dot org/womanasseen dot htm

Photo credit: Christopher Polk - JumpLine/ Getty Images