How “Accountability” Policies in Education Affect Teachers and What Communication Scholars Can Do to Support Them

In a new article published in NCA’s Communication Education, Anna M. Wright discusses some of the negative rhetoric surrounding teachers’ unions. Teachers’ unions are often accused of working against students’ interests. This article is part of a forum that has been made publicly available for the next few weeks by Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

The Accountability Movement

The 1983 report, A Nation at Risk, held public school teachers responsible for the problems within the public education system and argued that public education needed to be managed by the federal government for the good of the economy and national security. Wright describes A Nation at Risk as the first of many reports that have vilified educators and sought to apply the philosophy of business to schools, meaning that the effects of teachers on their classrooms could be quantified and measured.

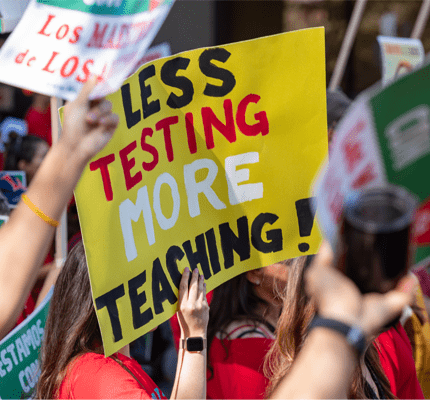

The goal of quantifying educational outcomes has led politicians to emphasize accountability in public education through federal programs, such as No Child Left Behind. Proponents of teacher accountability suggest that they are ensuring that teachers are educating students well. In reality, according to Wright, accountability shifts authority away from teachers and toward bureaucracy by implementing testing procedures and other accountability tools. Teachers and their unions have attempted to push back against these programs and the rhetoric of accountability, and thus are sometimes characterized in the media as not caring about their students or the quality of education being delivered.

Wright identifies five effects that the accountability movement has had on public education and teachers: deteriorating working conditions, de-skilling teaching, teacher dissatisfaction, teacher shortages in some areas, and harms to student learning.

Working Conditions

Although opponents of teachers’ unions argue that teachers are overpaid because of summer vacations, studies show that many teachers work nights and weekends and that some have second jobs. In addition to long hours, teachers often work in subpar buildings. In addition to these problems, Wright argues that the accountability movement has negatively affected teachers’ working conditions. Teachers must spend additional time preparing accountability reports and adjusting lesson plans to meet federal standards. Wright argues that these and other tasks associated with accountability reforms “come at the expense of pedagogical work,” meaning that teachers have less time to think about teaching.

De-Skilling Teaching

In addition to the negative impact on teacher working conditions, Wright also argues that the accountability movement has de-skilled teachers because it takes authority away from them and shifts it to the government. Governmental accountability programs emphasize standardized testing, which reduces teachers’ ability to be creative in the classroom. In addition, teachers may be forced to follow a common curriculum. Wright argues that these requirements mean that teachers rely less on their own professional skills and expertise.

Teacher Dissatisfaction

Wright notes that the loss of autonomy in the classroom has also contributed to dissatisfaction among teachers. Teachers often report feeling stressed and may feel that they cannot make decisions that are in the best interests of their students because of accountability measures. Teacher dissatisfaction may also be attributed to other factors, such as student behavior and school leadership. Teacher satisfaction can be improved through pay increases, administrative support, and other means.

Teacher Shortage

Some teachers move to different schools or leave education for different fields. Although teachers may change schools or leave the profession for a variety of reasons, such as family needs, some teachers report leaving because of dissatisfaction and better opportunities outside of the teaching profession. Wright argues that teachers leaving the profession has also led to teacher shortages in some subject areas and school types, which has incentivized states to reduce the professional requirements for teachers. Wright argues that reducing professional requirements through teaching programs, such as Teach for America, further de-skills the teaching profession.

Harms to Student Learning

Accountability measures often focus on the impact of individual teachers on students, sometimes called “teacher quality measures.” However, Wright argues that these measures rely on standardized testing, which does not capture the myriad ways that teachers impact the lives of their students or the circumstances of student learning, such as the resources available at school.

Teachers Fight Back

Wright also chronicles the ways in which teachers have fought accountability measures. Teachers’ unions have played a pivotal role in this fight, particularly through strikes. However, some members of the public have criticized teachers’ unions for fighting accountability and accused the unions of being bullies, of not caring about students, and of protecting members who are incompetent. As an example, Wright highlights the 2012 Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) strike, which occurred after Illinois attempted to limit what unions could strike over. Nonetheless, the CTU persisted in striking for benefits that would help the students, according to Wright.

What Communication Scholars Can Do

Wright suggests that Communication scholars should work with K-12 educators to better understand the needs of their schools and classrooms, particularly when conducting research about K-12 education. Wright suggests that these changes would signal the importance of Communication education in K-12 schools and provide support for teachers who feel dissatisfied and de-skilled in the current environment. Support for K-12 education by Communication scholars could ultimately promote public policy changes.