The Invitation to Learn the Uncomfortable Truth about Comfort Women

During and prior to World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army forced thousands of women into sexual slavery. Known as “comfort women,” many of them were just teenagers, atrociously abducted and kept in military brothels called the “comfort stations,” where Japanese soldiers physically abused, raped, and dehumanized them on a regular basis. Many of the women lost their lives. Some survived the atrocities yet struggled their entire lives with post-traumatic (physical and mental) issues, combined with complete cultural marginalization and social amnesia about their experiences. In a new article published in 2020 in NCA’s Quarterly Journal of Speech, Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager & Minkyung Kim challenge the lack of communication about the phenomenon, and apply “invitational rhetoric” to a documentary film and three memorials honoring comfort women. They consider what it would mean for the public to accept the “invitation” to understand these women’s experiences. The project was researched and written in hopes of bringing justice to the victims of one of the most controversial human rights violations that still remains unresolved.

In the post-World War II period, the Japanese government refused to be held accountable for what they did to the comfort women. The Japanese government’s role in enslaving and abusing these women was not publicly acknowledged until a 1991 lawsuit forced a public discussion about the women’s wartime experiences and possible reparations. After the lawsuit, the Japanese government still maintained that it was not legally responsible for the women’s well-being but established an Asian Women’s Fund (AWF) for their benefit. However, the rhetoric of the AWF still emphasizes language related to “honor” when discussing the women, which can reinforce stereotypes of being “dishonored” related to women who have been raped. As a result, the survivors are still struggling to have their experiences recognized and to secure an official apology from the Japanese government.

Invitational Rhetoric

Khrebtan-Hörhager and Kim argue that invitational rhetoric can create the opportunity for dialogue about survivors’ experiences. According to the authors, invitational rhetoric is based in equality, acceptance, and attempts to understand others’ experiences. However, they also argue that the equality necessary for invitational rhetoric is hindered by patriarchal societies that devalue women’s experiences and contribute to their objectification. Khrebtan-Hörhager and Kim write, “Motionless and mute, stripped of dignity, agency, and voice, comfort women simply did not have the means to partake in the narrative about the atrocities of wartime.” Many comfort women have been forced to stay silent about their experience. At the same time, the authors write, “comfort women have been treated as marginalized and socially excluded cultural others, undeserving of being honored or even remembered by the respective societies.” Such neglect calls for the urgent need to re-member the comfort women to the communicative spaces where they can be rhetors in their own right, in order to change the status quo.

Remembering Through Films

Films are powerful forms of visual rhetoric that can tell poignant stories about the comfort women’s experiences behind the scenes. Films can also serve as on-screen “invitations” to engage in non-discriminatory dialogues and actively embrace empathy. Tiffany Hsiung’s The Apology is a documentary about the devastating experiences of comfort women. The Apology focuses on the stories of three elderly women from South Korea, China, and the Philippines. In the film, the women are called “grandmothers” or “grandmas,” which, the authors note, “allows the audience to naturally correlate their old age with experience and wisdom… [and] creates a casual, community-and-care-based, almost familial frame of reference.”

In The Apology, Grandma Gil is an activist who is well-known for speaking about being forced to be a comfort woman and about the long-term effects of sexual slavery; Gil leads rallies in Seoul, South Korea, that demand an official apology from the Japanese government. Grandma Cao lives in a rural village in China and recently began speaking to a historian about the experience of being a comfort woman; in addition to collecting stories for a book, the historian also seeks justice for the women through protest. Finally, Grandma Adela resided in the Philippines and decided to speak about having been a comfort woman after decades of hiding this experience from family members. Adela wanted to join the protests in Seoul but died before being able to do so.

These grandmas’ stories point to the time-sensitive nature of the comfort women and invitational rhetoric. Khrebtan-Hörhager and Kim argue that it is important to invite the comfort women to remember their experiences and for society to acknowledge them while that is still possible. The grandmothers’ stories shared in the film invite the audience to understand their experiences. The film’s compelling narrative has inspired public support for an official apology and changed some people’s perceptions of the comfort women.

Memorials for Comfort Women

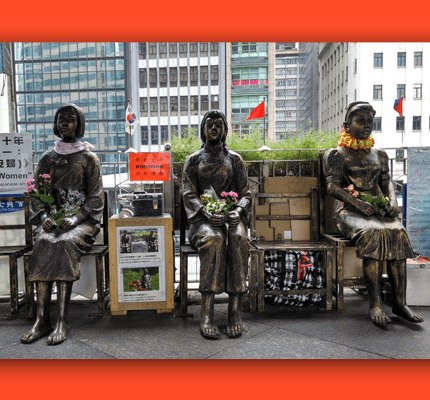

The authors also examine three different memorials in Hong Kong, Seoul, and San Francisco. The memorial in Hong Kong features statues of three women, representing China, South Korea, and the Philippines. Describing the statues, Khrebtan-Hörhager and Kim write, “Between the comfort women, there is a memorial station where flowers are placed to commemorate the victims of sex slavery. Each statue holds flowers and sits barefoot. The main purpose behind establishment of these statues is seeking official apology and bringing justice to victims.” The memorial’s prominent location near the city center invites people to learn about the women’s stories and experiences.

The memorial in Seoul was unveiled on the thousandth of what have been weekly protests at the Japanese Embassy. The memorial includes a young woman wearing Korean clothes and an empty chair that represents the comfort women who have died. The authors write that the chair also serves “as an invitation to the audience to join in, to sit down and reflect, share, and find their own voice.” Although the statue is still a site of contestation, public interaction with the memorial demonstrates changing public consciousness related to the comfort women’s experiences. Some visitors have adorned the statue in season-appropriate garb, such as scarves and hats, while others have left flowers.

The San Francisco memorial includes statues of three young women, with an older woman fondly facing them, as if she’s reminiscing about her lost youth. According to Khrebtan-Hörhager and Kim, “[the older woman’s] presence suggests a cross-generational connection and the importance of honoring the past for the present and the future.” San Francisco is a sister-city to Osaka, Japan, but has resisted Osaka’s request to remove the memorial. Thus, the memorial’s presence is an invitation both to remember the comfort women and to demonstrate resilience as the women fight injustice.

Conclusion

In the decades following World War II, comfort women were often silenced about what they had endured because of the societal stigma associated with being raped. Their active sharing of narratives were often silenced by the media, politicians and the Japanese. The film and memorials discussed in this article are bringing attention to the experiences of the comfort women, creating a new communicative space for the public to hear their story. Khrebtan-Hörhager and Kim argue that more invitational rhetoric is needed to both honor the comfort women and spur social change.