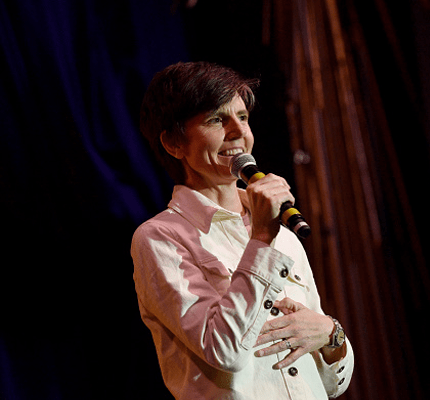

Comedian Tig Notaro Subverts Norms Related to Breast Cancer Through Raw, Honest Storytelling

Tig Notaro is a woman comedian known for deadpan comedy. In 2012, Notaro experienced a series of unexpected life events within a few months: a devastating bacterial infection, the death of a parent, and a breast cancer diagnosis that resulted in a double mastectomy. In a new article published in Text and Performance Quarterly, Darren J. Valenta argues that Notaro used the rhetorical trope bathos to subvert the idea of a “she-ro” who is fighting cancer on the comedy album, Live, and in parts of the comedy special, Tig Notaro: Boyish Girl Interrupted.

The She-ro

In the 1980s and ’90s, activists transformed breast cancer from a stigmatized disease to one associated with a social movement that focused on breast cancer survivors. During this time, breast cancer became defined by the pink ribbon created by the Estée Lauder companies and Self magazine. Through the pink ribbon, organizations and corporate sponsors could capitalize on femininity.

One of the biggest proponents of the pink ribbon is Susan G. Komen for the Cure. Susan G. Komen has raised billions for breast cancer research, outreach, and advocacy, but also has been criticized by some breast cancer activists for profiteering and “pinkwashing,” or using philanthropy for marketing purposes. Critics point out that Susan G. Komen partners with corporations to raise money, such as through the purchase of yogurt cups, and that while these activities primarily benefit Susan G. Komen’s corporate partners, more money for breast cancer research and support could be raised through direct donations.

Valenta argues that pink ribbon culture envisions a particular kind of breast cancer survivor who is youthful, feminine, and often white. Specifically, Valenta defines the she-ro as “an ideal breast cancer survivor who exhibits optimism, selfishness, and guilt.” The she-ro is optimistic about surviving breast cancer, but also is allowed to be selfish (but must apologize for being selfish even in the face of a cancer diagnosis) and feels guilty about failing to adhere to the she-ro narrative, about the bodily changes cancer causes, and about not being able to fulfill idealized gender norms.

Bathos

According to Valenta, as a literary and rhetorical trope, bathos is defined as “the vulgar, mundane, and flawed aspects of living.” How does bathos appear in text or performance? It is language that appears to be out of place or in the wrong context. In particular, bathos occurs when moving from serious language to trivial or inappropriate language. For example, Valenta suggests that the joke, “A severed foot is the ultimate stocking stuffer,” is an excellent example of bathos because it juxtaposes the serious (a severed foot) with the trivial (holiday stockings).

Tig Notaro and the She-ro

Valenta writes that Notaro uses bathos in a number of ways. In Live, Notaro begins the album with, “Hello. Good evening. Hello. I have cancer. How are you?” Valenta argues that Notaro uses bathos by inserting “I have cancer” into “an otherwise stock greeting,” where it doesn’t belong. Furthermore, Notaro addresses the audience in unexpected ways. When discussing painful breast biopsies, Notaro tells the audience, “It’s ok. It’s ok. It’s gonna be ok. It might not be ok, but I’m just saying. It’s ok. You’re gonna be ok.” According to Valenta, Notaro violates the usual optimism of the she-ro by saying that “it might not be okay.”

On the same comedy album, Notaro also discloses an incident when someone mistook the comedian for a man. Describing the incident, Notaro said, “I was just like, ‘I just got diagnosed with breast cancer. In both breasts. That’s how much I’m not a man.’” Valenta argues that a normal incident of mistaken identity becomes something more because Notaro’s breasts, a typical marker of womanhood, are also a source of additional pain because of the breast cancer diagnosis. By not realizing that Notaro is a woman, the individual in the story unintentionally denies the reality of Notaro’s experiences as a woman with breast cancer.

In Boyish Girl Interrupted, the second half of the special focuses on Notaro’s breast cancer diagnosis and double mastectomy. After having a double mastectomy, Notaro chose not to have reconstructive surgery. Valenta writes that this choice is itself a violation of norms that encourage women to get reconstructive surgery and “regain the conventional image of a woman” after breast cancer. In the special, Notaro recounts an incident in which a TSA agent misidentifies Notaro as a man. Notaro does not apologize for the confusion or offer an explanation, but, instead, “push[es] her chest out toward the imaginary TSA agent, and casually cast[s] her gaze around the room.” According to Valenta, by doing this, Notaro rejects the she-ro norms that call for guilt for failing to adhere to gender norms.

Later in the special, Notaro’s mastectomy scars are on full display as Notaro stands shirtless in front of the crowd. Valenta argues that this choice “violates the very core of dominant breast cancer culture’s mandate to hide the uncomfortable truths about living with and surviving breast cancer.” Thus, Notaro’s decision to both forgo reconstructive surgery and publicly display mastectomy scars challenge the dominant culture around breast cancer that depicts women surviving breast cancer, unchanged, with both breasts intact, even though this is not the case for many survivors. In this way, Notaro also represents survivors who are not often seen in public representations of breast cancer. Valenta writes that in closing the set while topless, Notaro again uses bathos. Notaro returns to mundane subjects, such as a hatred of travel, and never mentions being topless or having breast cancer again during the special.

Conclusion

Live and Boyish Girl Interrupted demonstrate that pink ribbon culture and the she-ro do not define all experiences with breast cancer. Notaro’s autobiographical comedy subverts typical stories about breast cancer and illness through the use of bathos. Valenta concludes that by sharing raw, real experiences with cancer through comedy, “Notaro showcases the endless potential of the pairing of bathos and stand-up comedy as a potent critical tool capable of instigating change.”