Critical War Play

In the years since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, one of the most popular and commercially successful video game genres has been the military shooter. Typically played from either the first- or third-person perspective, these titles locate players on historic and near-future battlefields, arm them with a bevy of weapons, and task them with achieving tactical objectives in scenarios ranging from conducting surveillance runs to engaging in close-quarters combat to spearheading vehicular battles. Not surprisingly, the overwhelming majority of shooters published by major firms such as Activision, Ubisoft, and Electronic Arts celebrate America’s endless War on Terror as a grave but necessary and patriotic undertaking. The post-9/11 shooter’s gameplay design and marketing formula established a jingoistic genre that netted billions of dollars for the industry’s biggest firms.

Yet, despite these commercial achievements, we are beginning to see cracks emerge in the façade of this popular form of militainment. Indeed, the cultural industries’ battle for the “hearts and minds” of citizen-consumers has never been a seamless campaign; inevitable contradictions emerge from such a widely distributed undertaking, and with these incongruities come opportunities for social resistance. Enter Spec Ops: The Line (2012).

At first glance, Spec Ops, designed by Yager Development and published by 2K Games, looks like a prototypical shooter; initially it is reminiscent of industry juggernauts Call of Duty, Battlefield, and the Tom Clancy-brand titles. In the game’s single-player campaign, one plays as U.S. Army Captain Martin Walker who is charged with locating the soldiers of the 33rdBattalion who went missing after cataclysmic sandstorms obliterated the city of Dubai. Alongside fellow Delta Force operatives Lt. Adams and Sgt. Lugo, Capt. Walker (the player) traverses the decimated and sand-swept ruins for signs of survivors and for Col. John Konrad, the commanding officer of the 33rd. The conceits of the game’s narrative setup and its familiar cover-and-fire combat system evidence nothing we have not seen elsewhere, begging the question, How is Spec Ops different from every other military shooter on the market?

In seeming response to this question, Spec Opsintroduces narrative uncertainties and gameplay oddities foreign to the shooter genre. For example, Walker and company are forced to fight and kill fellow American GIs; Walker is increasingly plagued by hallucinations that cloud his judgment; the team slaughters unarmed civilians; and even the game’s interstitial loading screens taunt the player with rhetorical questions such as, Do you feel like a hero yet? As the players make their way through the campaign, it becomes evident this game is not what it purports to be. Indeed, Spec Ops might be the game industry’s first major, anti-war military shooter.

In particular, the game’s brutal representations, its references to popular war media, and its illusory opportunities for player choice create a discordant feeling that lays bare the problematic ease with which most video war games indulge in their nationalistic power fantasies. The result is a video game that wields its affective distance as a critique of the necessary illusion all military shooters trade in, but one that so few acknowledge.

Mise-en-scène of Madness

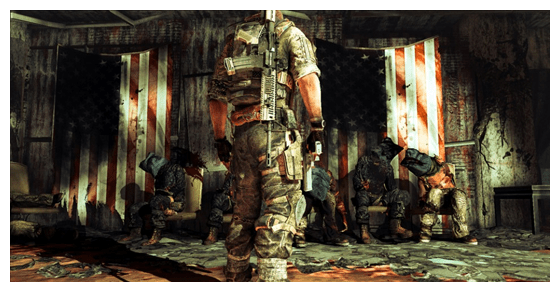

The game’s level construction and its avatar design underscore Capt. Walker’s descent into madness. By situating the player in a crumbling city amid the suffocating vestiges of western civilization, and by altering Walker’s physical appearance over the course of the game to reflect his transformation from a competent squad leader into a murderous monster, Spec Ops presents a damning indictment of the representational practices of “othering” typical of post-9/11 combat games set in the Middle East. That is, rather than presenting players with endless waves of dark-skinned “evil-doers” to shoot, the player watches as Walker becomes the cause of the conflict, not the solution to it.

Critical Intertextuality

Borrowing in equal measure from Joseph Conrad’s 1899 imperialist novella Heart of Darkness and Francis Ford Coppola’s post-Vietnam cinematic epic Apocalypse Now (1979), Spec Ops abounds with allusions to other popular war media. The game’s intertexual referencing of militainment serves two purposes: first, it situates the game within a larger cultural milieu of combat fare; second, and more critically, it breaks the diegetic fourth wall by addressing the players directly and repeatedly, reminding them they are playing a game. Contrary to received design wisdom, such a strategy alienates the players from Walker. That is, in lieu of engendering identification by closing the gap between the players and their avatars,Spec Ops creates disidentification by insisting on their separate identities.

Illusion of Choice

The “freedom” at the heart of the Spec Ops experience is summarized nicely by one of its loading screen’s title cards: “Freedom is what you do with what’s been done to you.” Spec Ops makes the player feel trapped by denying any ability to affect meaningful change. The player simply has no good choices. Moreover, every move leads to worse results and harder choices. Thus, along with its bleak setting and the inability to identify as Walker, dissonant gameplay is achieved partly by one’s inability to manage the hopeless situation.

Games are inherently attractive because players enter into them freely; that is, it cannot be called “play” if one is forced to participate. Many gamers enthusiastically play shooters because they can exercise control over a seemingly chaotic situation, round after round, level after level. Of course, the same cannot be said of actual war, which is often indiscriminate, messy, and final. Spec Ops’ inclusion of collateral damage, fratricide, PTSD, and war’s attendant horrors remind us there is a wide experiential gulf between consuming those combat stories fit to be sold and reflecting on how combat victories are actually secured and their lasting human effects. When such omissions move from the periphery to the center of the commercial gaming experience, the “right” way to play Spec Ops—–with the kind of social resistance to militainment’s pleasures and the consciousness-raising it proposes—first begins not with learning how to shoot, but with asking what it means to do so.